After The Simla Agreement was signed and the Bangladesh crisis had been resolved, Indira Gandhi once again turned to her crisis man, D.P. Dhar, to tackle another looming crisis—the economy. The heavy military expenditure during the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 had taken a toll on the country. India was about to mark twenty five years of independence and, after four unremarkable five-year plans, the pace of development wasn’t quite what the political leadership had hoped for.

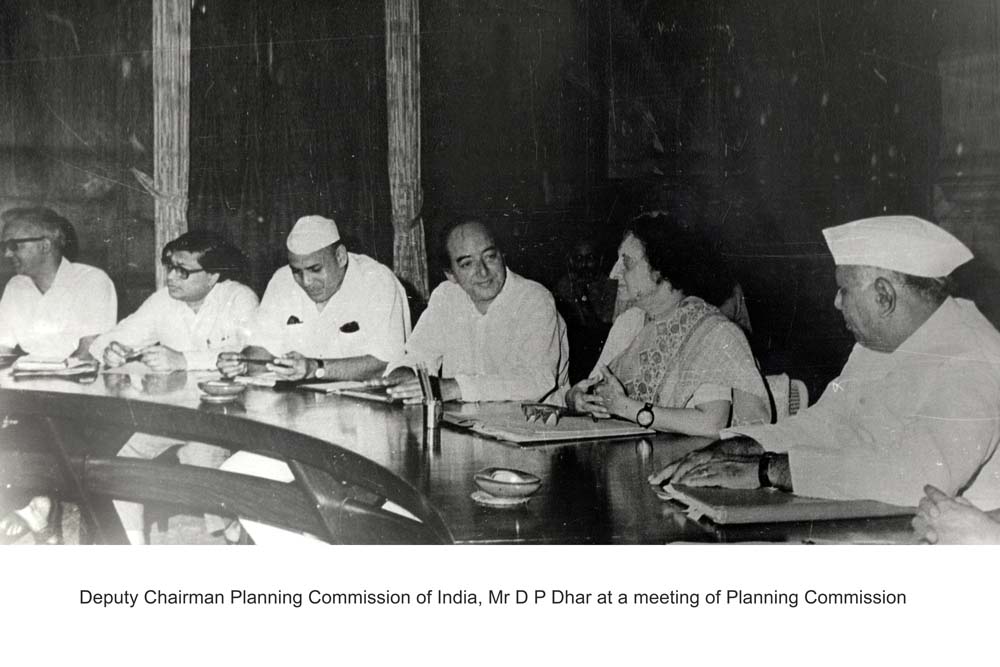

On July 23, 1972, Durga Prasad Dhar was appointed Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission and Minister of Planning in charge of India’s Fifth Five-Year Plan. It was a Herculean task and it has been suggested that D.P. was the only one Mrs. Gandhi trusted with it at the time.

Minister of Planning

As Minister of Planning, D.P. Dhar was part of the Union Cabinet. Although he was not an economist by training, he quickly settled into his new position in Yojana Bhawan. In the preface to his only book, ‘Planning and Social Change’, published posthumously in 1976, Dhar writes:

“Some may question my credentials for this task. They may do so but I have no regrets or apologies to offer them. I may not be a professional sociologist or economist or political theorist. But I am an Indian and a politician and hence have a right to talk about matters that concern me even if this means my poaching in the groves of Academe. Planning and social change are too important to be studied by professional social scientists. In fact even the academic disciplines of economics and sociology are too important to be left to them. To paraphrase – social scientists are not special sorts of persons; every person is a special sort of social scientist (Dhar, 1976, p. xiv).”

His political thought had been deeply influenced by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, and like him, he viewed planning to be essential to social and economic transformation. Nehru was the main proponent of the Indian Planning Commission when it was first set up in 1950. He believed planning was the key to India’s future development. Dhar espoused these views, stating that his own views on planning were “an elaboration on the vision of development that Panditji unfolded (Dhar, 1976, p.xiv).”

D.P. Dhar ensured that his team at the Planning Commission included the top economists and sociologists in the country. The economist Vijay Kelkar, who worked as a consultant at the Planning Commission at that time, recounts:

“That was the most lively time, if I may say so, in the Planning Commission after many, many years. He [Dhar] had brought in all sorts of people into the Planning Commission. It was throbbing with intellectual activity. I remember there was B.S. Minhas. There was Arun Shourie as a consultant. I was also there as a consultant. Then Nitin Desai, who later on became the highest level undersecretary to the UN, was also working there. And he had brought Mr. Vasant Rajdhakshya [former Hindustan Unilever Chairman]. So it was really throbbing with energy, throbbing with ideas and he [Dhar] encouraged everybody. He didn’t stop any ideas from flowing.” (Read Dr Vijay Kelkar’s full interview here.)

Approach to Planning

D.P. Dhar believed in planning as a way to tackle the vast economic and social disparities in India. He writes early in his book:

“…We cannot view economic problems in isolation from the social and political matrix in which they are embedded. Planning in India is not merely a managerial device but an instrument of social change and, if I may be allowed to use the word, of revolution.” (Dhar, 1976, p.2)

He was focused on equality and creating regional balance. He believed that it was important that no region of India should be excluded from the development process. Dhar had a deep understanding of the Marxist framework and saw secularism, modernisation, and scientific methods, as the basic pillars of planning.

Like his mentor, Pandit Nehru, Dhar was suspicious of the profit motive. In 1973, he controversially argued for the wholesale trade of food grains. His colleague, B.S. Minhas, even resigned over the issue. D.K. Barooah later explained the reasoning behind Dhar’s wholesale grain policy:

“All manner of ills have been attributed to this policy. But whatever one may feel about the merits of the proposal one must recognise the logic that led D.P. to place such importance on it. He believed that our drive towards prosperity and self-reliance would continue to be a rough one unless food supplies to the urban masses and to the poor in rural areas could be guaranteed even in a bad year. Otherwise the all too familiar sequence of inflation, erosion of resources and cutbacks in investment would be repeated. In his view, the only way to ensure price stability and equitable distribution in a bad year was public distribution, the only way to run public distribution was public procurement in good and bad years and the only way to secure public procurement at a reasonable cost was the takeover of wholesale trade.” (Read DK Barooah’s full article here)

It was a bold move, and given the vested interests in the private sector, it took immense courage to put forward. The economist Pulin B. Nayak, in his extremely insightful paper ‘Planning and Social Transformation: Remembering D. P. Dhar as a Social Planner’, writes about the policy in detail:

“This was too big an issue that D.P. dared to take on, and the vested interests in this sphere were, and still continue to be, after more than four decades, far too entrenched. This particular move of D.P.’s was doomed to failure. But if one considers the simple fact that when, recently, the price of onions had shot up to Rs 80 per kilo in the retail market, it was also known that the growers would be getting no more than Rs 16 to Rs 20 a kilo, it becomes obvious that there is a huge spread that accounts for the surplus going to middlemen and wholesalers, which is a necessary characteristic of the market mechanism. It is this surplus generation that D.P. was interested in curbing. This is a critical feature of the monopolistic practices adopted by the cabals of ‘aadtiyas’ in rural mandis. The problem continues to be of relevance 40 years after D.P. had tried to raise the issue.”

Indo-Soviet Trade

As Planning Minister, Dhar also tapped into his expertise in Soviet relations and signed trade and protocol agreements with the USSR.