In 1937, eighteen-year-old DP left Kashmir to pursue a degree in law at the University of Lucknow. At the time, Lucknow was burgeoning with political activity and much of it was concentrated at the university.

Lucknow University

His years in Lucknow were to have a profound impact on his life. It was here that he first began to nurture a lifelong passion for Urdu poetry and literature. He was already fluent in Persian and could recite the Diwan-e-Ghalib and the poetry of Mir Anees from memory (he would later write poetry in Urdu under the pen name ‘Raunaq Kashmiri’).

He read Marx and Engels and resonated with their ideas as he considered the feudal and exploitative society he had left behind in Kashmir. He also became friends with members of the recently founded Progressive Writers’ Association and grew particularly close to Ali Sardar Jafri, Sajjad Zaheer and Kaifi Azmi. Many of the Progressive writers were communists and had strong ties to the Communist Party. DP stopped short of joining them, fashioning himself more in the style of his idol, Jawaharlal Nehru, and turning instead to Fabian socialism.

President of the Student Union

The student union elections were a major event at the university. Dhar ran as an independent candidate, with outside support from the Communist Party of India garnered through Ali Sardar Jafri, and beat the candidates from the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League to become President of the Student Union.

His election garnered attention even in Delhi, with Jawaharlal Nehru taking note of the promising young Kashmiri Pandit lawyer (like Nehru himself) who was making a mark in Lucknow. Dhar was eager to meet Nehru and invited him to speak at the university. As Dhar’s son, Vijay, recounts:

“As President of the Union he [DP Dhar] decided to invite Jawaharlal Nehru to speak. Now, where does the money come from? So he wrote home to get 800 rupees… at that time. So I’m sure his father was a little furious. But he sent him the money and that is where he first met Panditji. And Panditji just took to him. He was very, very fond of him. He was one of only two people who used to call him Durga and not DP.”

The two struck up a correspondence that lasted till Nehru’s death in 1964.

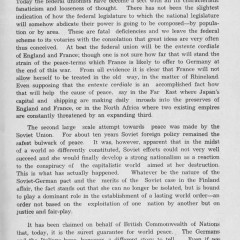

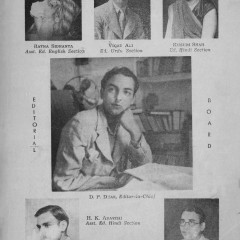

Dhar was also the first student Editor-in-Chief of the Lucknow University Union Journal and edited the March 1940 edition. The editorial, written shortly after the outbreak of World War Two, shows Dhar’s singular passion for India’s independence from British rule and his socialist bent of mind.

He writes of the British call for India to join the war effort:

“It has been claimed on behalf of British Commonwealth of Nations that, today, it is the surest guarantee for world peace. The Germans and the Italians have, however, a different story to tell. Even if we concede that the relation between Great Britain and the Dominions, India—the colonies, is as it should be, the very unequal division of resources and living space as between the old empire and the rising one, is a sufficient cause for unsettlement. Therefore, with the best of intentions the British Empire, by the mere fact of its being first in the field, cannot contribute to the cause of collective security.”

And then he categorically answers the question all Indians were asking at the time:

“But what has the Indian youth to do in these circumstances, when every avenue towards a better order has been closed? The answer seems to be to harness all his strength towards the attainment of freedom.”

Read the full text of the editorial here.

Graduation and back to Kashmir

D.P. Dhar graduated with an LLB from the University of Lucknow in 1940. He intended to return for an LLM but his plans changed with the sudden demise of his father, Srikant Dhar. At the age of 22, DP suddenly found himself the head of the family, with a wife, mother and two younger siblings to provide for. He began practising law in Srinagar but, much like his role model Nehru, his career as a lawyer never quite took off. He too was destined for politics.