In August 1971, D.P. Dhar had been recalled from his ambassadorial assignment in Moscow to help India manage the deepening crisis in East Pakistan. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi appointed him Chairman of the Policy Planning Committee in the Ministry of External Affairs, a one-man committee created specifically to handle the liberation of Bangladesh. In his new role, Dhar bypassed the External Affairs minister, Swaran Singh, and reported directly to Mrs. Gandhi.

The New York Times described Dhar’s influence as follows:

“As chairman of the Policy Planning Committee of the Foreign Ministry, Mr. Dhar is at the apex of the triumvirate of Kashmiri Brahman advisers to Mrs. Gandhi, herself a Kashmiri Brahman. At the bottom are Foreign Secretary T. N. Kaul and P. N. Haksar, the Prime Minister’s private secretary. Mr. Kaul and Mr. Haksar are associated with many decisions Mrs. Gandhi makes, but Mr. Dhar seems one step above them — he makes decisions for her.”

Liberating Bangladesh

D.P. Dhar is credited with being the chief architect of India’s diplomatic strategy in Bangladesh. P.N. Dhar, in his book ‘Indira Gandhi, the ‘Emergency’, and Indian Democracy’, writes of D.P.’s role in great detail:

“After much reflection Mrs Gandhi gave the task of helping the provisional government [of Bangladesh] in these matters to D.P. Dhar who was then Indian ambassador to the Soviet Union. D.P. was recalled and appointed chairman of a policy planning committee under the auspices of the ministry of external affairs. This one-man committee was solely concerned with the Bangladesh crisis.

D.P.’s task was formidable but he was eminently qualified to undertake it. His winsome manner, his brilliant sense of humour, and his acute intelligence were all invaluable assets in his new job. He had the gift of flavouring his exposition of the same theme with subtle nuances in order to reassure and satisfy interlocutors of different shades of opinion. He also had the rare ability to listen to fools as well as knaves calmly, without losing his patience or showing signs of irritation. He could talk to soldiers, politicians, journalists and radicals of different hues in their own idiom. The five Khalifas, who at first refused even to meet him because they suspected him of being a communist, ended up as his admirers. Besides face-to-face meetings with various Bangladesh leaders, D.P. institutionalized his communication with the provisional government by stationing an officer in Calcutta for regular contact with the provisional government in Mujib Nagar.”

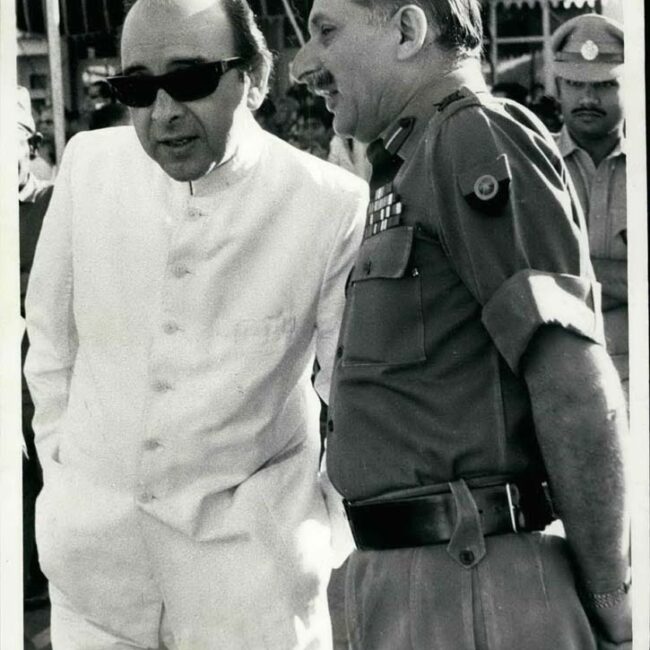

Through the course of the war, D.P. Dhar worked closely with General (later Field Marshal) Sam Manekshaw, whom he had first met in Kashmir in 1947 during the Pakistani invasion of Kashmir. The duo got along famously, sharing in equal measure a deep patriotism for India and a deep love of Scotch.

Through the course of the war they worked closely together on military strategy as General Manekshaw represented all the military chiefs at the daily meetings of The Foreign Policy Planning Committee that was chaired by Dhar. Dhar traveled constantly between Delhi, London, Moscow and Calcutta between July and December 1971. He was Manekshaw’s main point of contact with the government.

Manekshaw and Dhar also crafted the disarmament agreement between India and Bangladesh’s provisional government involving the reorganisation of the 100,000 strong Bengali guerrilla force and the withdrawal of Indian troops.

Soviet Involvement during the 1971 War

On December 3, 1971 Pakistan launched Operation Chengiz Khan, marking the official start of the Indo-Pakistan War. The Indian response was a defensive military strategy in the West while simultaneously launching a coordinated and decisive offensive in the East. On 5 December, the United States began attempted twice for a UN-sponsored ceasefire, but these were vetoed by the USSR in the UNSC. On December 6, 1971, India officially recognised the nation of Bangladesh.

On 8 December, the United States dispatched a ten-ship naval task force, the US Task Force 74, into the Bay of Bengal. The task force was to be headed by USS Enterprise, at the time and still the largest aircraft carrier in the world. At the same time, UK dispatched its aircraft carrier HMS Eagle in the Arabian Sea. India would be caught in a pincer attack with the US in the Bay of Bengal, the UK in the Arabian Sea, and Pakistan on land.

It was within this context that DP Dhar urged Indira Gandhi to activate the secret provision in Article 9 of the Indo-Soviet Peace Treaty that he had negotiated earlier that year, under which the USSR was bound to help India in case of any external aggression.

Article 9: ‘In the event of either Party being subjected to an attack or a threat thereof, the High Contracting Parties shall immediately enter into mutual consultations to remove such threat and to take appropriate effective measures to ensure peace and security of their countries’.

At a meeting chaired by Mrs. Gandhi to assess the implications of the Seventh Fleet’s presence in the Bay of Bengal, D.P. Dhar told her, “What is the point of India having signed the Indo-Soviet Treaty if India cannot call this bluff?” Then, on December 14, P.N. Haksar cabled Dhar in Moscow saying it was necessary “to make a public announcement carrying the seal of the highest authorities in the Soviet Union that involvement or interference by third countries… cannot but aggravate the situation”. Dhar passed on the message to the Kremlin, who “sent a top-secret message to Nixon” warning the U.S. “against involvement or interference”.

The Soviets dispatched a nuclear-armed flotilla from Vladivostok on December 13, 1971. The Soviets then intercepted a communication from the commander of the British carrier battle group, Admiral Dimon Gordon, to the US commander: “Sir, we are too late. There are the Russian atomic submarines here, and a big collection of battleships.” The British ships then moved towards Madagascar while the larger US task force stopped before entering the Bay of Bengal.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s release

As the crisis in Bangladesh unfolded, Indira Gandhi and her quartet of Kashmiri advisors— DP Dhar, PN Haksar, PN Dhar, and TN Kaul—were trying figuring out how to get the Bangladeshi leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman back to his country alive. The Pakistani military court had already tried him and issued a verdict of death by hanging. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s military dictator, General Yahya Khan, had decided to step down. He sent word to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was at the UN in New York, to return to Pakistan immediately and take over as martial law administrator.

It was within this context that Sashanka S. Banerjee, a diplomat in the Indian mission in London in 1971-72, recounts in an article for The Wire the thrilling backchannel talks involving D.P. Dhar that eventually led to Sheikh Mujib’s release:

“Bhutto’s Washington-Rawalpindi flight was scheduled for a refuelling stopover at Heathrow airport in London.

Having secured insider information about Bhutto’s journey home, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called an emergency meeting of the war cabinet in New Delhi at her office in South Block. She wanted, with the utmost urgency, to secure a contact who would be present for Bhutto’s arrival at Heathrow, so she could get the only piece of intelligence India was looking for – what did Bhutto think about Mujibur Rahman being sentenced to death by a Pakistan military court?

The meeting was attended by Durga Prasad Dhar, head of policy planning in the Ministry of External Affairs; Ram Nath Kao, chief of RAW; P.N. Haksar, the prime minister’s principal secretary and T.N. Kaul, the foreign secretary.

It was under Mrs Gandhi’s instructions that Muzaffar Hussain – the former chief secretary of the East Pakistan government, the highest ranked civil servant posted in Dhaka as of December 16, 1971 who had subsequently become a POW in India – was lodged as a VIP guest at the official residence of D.P. Dhar. His wife, Laila, who was visiting London when war broke out on December 3, 1971 couldn’t return home and was stuck there. Both husband and wife (in Delhi and London) were communicating with each other through diplomatic channels. I was assigned the job of a VIP courier. Thanks to conducting several back and forths between the two, I soon established a useful rapport with Laila Hussain.

The prime minister was very much aware that Laila and Bhutto had been intimate friends for a long time and continued to be so. It was felt at the PMO that she was well placed to play a key role in a one-off diplomatic “summit” at the VIP lounge, the Alcock and Brown Suite, at Heathrow airport.

I had met Dhar several times in London during the nine months – from 25 March 1971 to 16 December 1971 – that the Bangladeshi liberation struggle was on. It was at that time that we became friends. He was an unassuming, refined literary personality, extremely well-versed in Urdu poetry. My love of Urdu poetry from my days at Osmania University in Hyderabad was what resulted in our unlikely friendship – despite the huge gap in official hierarchy. D.P. was a cabinet minister and I was a mere bureaucrat.

Just two days before Bhutto was to arrive in London I got a telephone call from D.P. in Delhi. He wanted me to inform Laila that Bhutto had been appointed the chief martial law administrator (CMLA) of Pakistan and that he was on his way to Islamabad from Washington. His flight would be stopping at Heathrow airport for refuelling. I was supposed to persuade Laila to meet Bhutto – for old time’s sake – and ask him, in his capacity as the CMLA, if he could help in getting her husband released from Delhi. Laila knew only too well that I was aware that she had had a relationship with Bhutto in the past. Seeing how the discussions progressed would be a matter of great interest to us. India wanted to know only one thing: what Bhutto was thinking about Rahman, whether to release him to return home, or carry out the military court’s verdict of death.

I succeeded in setting up the meeting. The two long-lost friends, Laila and Bhutto, met at the VIP lounge at Heathrow airport. The meeting was marked by great cordiality. It was as convivial as could be. Without a doubt, the back-channel encounter turned out to be a meeting of great historic significance. It was well and truly a thriller, a grand finale to this narrative.

Bhutto was quick on the uptake. As he responded to Laila’s emotional appeal for help in getting her husband released from Indian custody, he also cottoned onto the fact that the lady was in fact doing the Indian government’s bidding. With a twinkle in his eye, Bhutto changed the subject. And pulling her aside, he whispered to Laila a very sensitive, top secret message for the Indian prime minister. Sourced from Laila, I quote: “Laila, I know what you want. I can imagine you are [carrying a request] from Mrs. Indira Gandhi. Do please pass a message to her, that after I take charge of office back home, I will shortly thereafter release Mujibur Rahman, allowing him to return home. What I want in return, I will let Mrs. Indira Gandhi know through another channel. You may now go.”

Bhutto over-ruled the death sentence handed out by the military court and released Mujibur Rahman on January 8, 1972. On his return, Mujib took charge as prime minister of Bangladesh on January 10, 1972.

The Hero of Bangladesh

In 2012, Bangladesh’s President Zillur Rahman conferred the Liberation War Friendship Honour posthumously to Durga Prasad Dhar in recognition of his pioneering role in concluding the Indo-Soviet Treaty of 1971, mobilising international support in favour of Bangladesh and playing a special role in support of the Liberation War. His son, Vijay Dhar, received the award on his behalf.