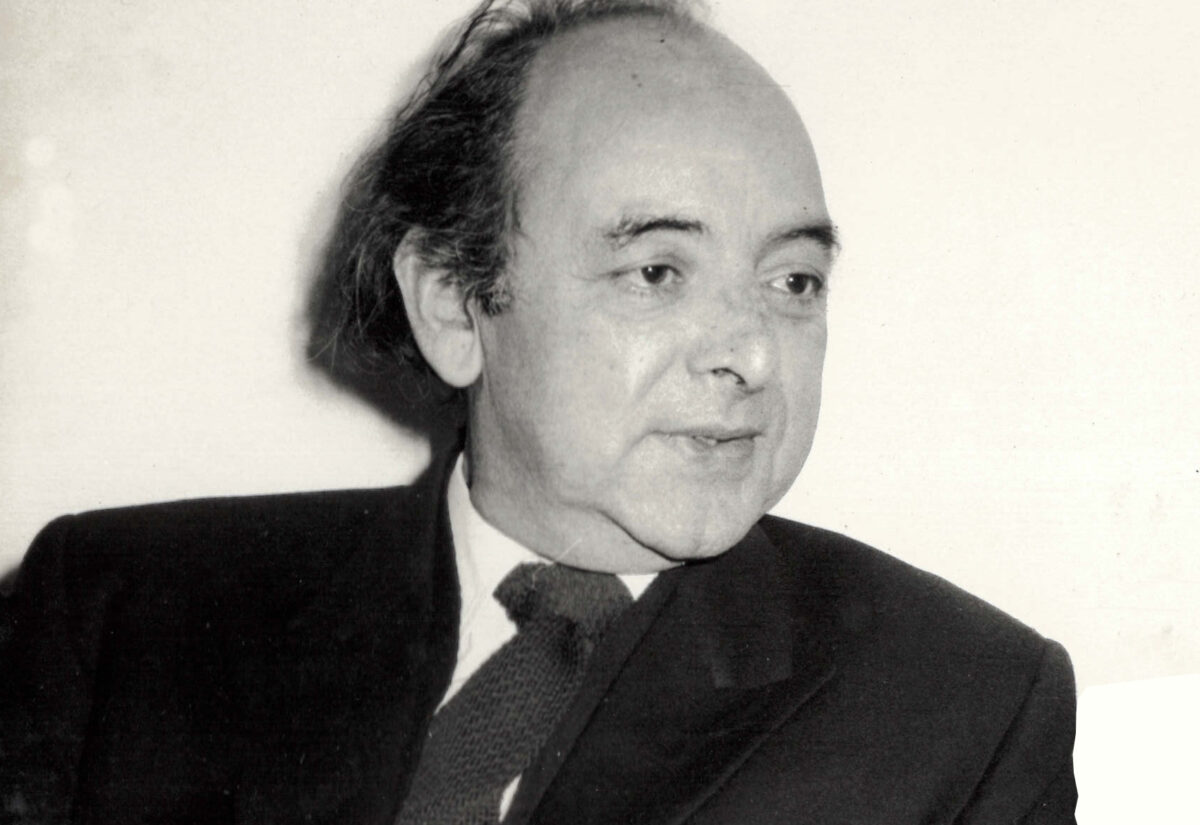

D P Dhar was my first political ambassador, though alas, only for a brief while. It was his second stint in Moscow and he was obviously not happy to go there again, after having been a hero of the Bangladesh war and the Simla Agreement. He had grown in stature beyond being an ambassador to Moscow.

But when he found that Indira Gandhi’s political calculations had landed him in Moscow, he put his heart and soul into his job. His assignment was cut short when, while on a visit to Delhi, he succumbed to his heart ailment. But he had convinced us during a short period that he had a grand design for Indo-Soviet relations and that each of us in his team in Moscow had a role to play. In my own case, he had made up his mind even before he met me that he would shift me from my administrative job to a political one. It came as a surprise to me as I was enjoying the power of the head of chancery, a post equivalent to a district collector in the administrative Service. At a fairly junior level, the post gives the incumbent a special position in the embassy. Even senior colleagues were deferential to the head of chancery as he had the power to help or harm in administrative and financial matters. In fact, I was involved in the whole process of settling in of the new ambassador because of my appointment. But Dhar broached the subject of a change within days of his arrival, saying that in Moscow, I should not waste my time on curtains and carpets. I was not convinced initially and my immediate boss, Peter Sinai, was not keen that there should be a change. But when I realised that he had a specific plan for me to work with him directly, I decided to take the plunge. But he was gone even before I completed my first assignment, a study of the Soviet policy in South-East Asia.

Dhar took no time to settle in his new job, as he had become an expert on the Soviet Union not only during his first assignment as ambassador, but also during his days as the Chairman of the Policy Planning Committee, a cover for Bangladesh troubleshooting.

He visited the Soviet Union several times during that period in the company of General (later Field Marshal S H F J) Manekshaw and Joint Secretary for East Europe, A P Venkateswaran, who later became foreign secretary. In fact, Venkateswaran tells the story of a Soviet general, who was curious about the composition of the Indian delegation to the crucial talks on Bangladesh. The general could not figure out what Venkateswaran’s role was in the whole affair. Venkateswaran, in his inimitable style, told the general that his role could be described only in Hindi or Tamil and not in any other language. In Hindi, he said he was Dhar’s ‘spoon’ and in Tamil, he was his ‘water jug.’ How would the general know that the words chamcha and kooja both meant constant companion to do odd jobs? He remained as confused as ever.

Dhar and Rani bhabhi (the only ambassadorial wife, who insisted that she should not be called ‘madam’) were legendary for their hospitality. They entertained extremely well, even more than some career ambassadors. Fotedar, his private secretary, took care of the guests, sparing no effort or expense to make them happy. Even friends of friends of the ambassador stayed at the residence and some of them did not even recognise him. The guests, who arrived in the night, would be put up in their rooms and Dhar and his wife would meet them only at the breakfast table next morning. One of the guests once asked them when they had arrived, thinking that they were also guests at the residence.

Dr Shelvankar, the journalist turned diplomat, Dhar’s successor after his first term and his predecessor before his second term, and his wife, Mary, an Irish lady, were not particularly popular in Moscow. Mary Shelvankar had quite a reputation for bossing over Shelvankar. She had occupied the ambassador’s office room in the residence and sent the ambassador to a security guard’s room in the basement. Mary took decisions on all administrative matters in the embassy and the ambassador would send me to her whenever I raised administrative matters with him.

Dhar was obviously aware of the situation when he visited Moscow on one occasion as the planning minister. Shelvankar and Mary hosted a reception for him at the residence and they were at the receiving line when Dhar arrived. Mary was in a splendid Kanjeepuram sari and looked very proud of herself as she greeted Dhar. “Mary, you look gorgeous!” said Dhar. Mary put on some modesty and said: “Oh am I alright DP? Do I really look like the ambassador’s wife?”

“What do you mean Mary? You look like the ambassador’s husband!” said Dhar, much to the delight of some of us who overheard him.

Once Dhar called me to his residence on a Sunday and when I arrived, he was lying flat on the terrace with just a towel around him and someone was giving him a massage. Even though the masseur asked me to go and talk to Dhar, I made a quick retreat, thinking that I would wait till he finished his massage and bath. I went over to the embassy garage and started washing my car. After a little while, someone tapped me on my shoulder and I turned around. It was Dhar, immaculately dressed in a pinstriped suit. “Am I now properly dressed for you to talk to me? I believe you ran away since I was not dressed,” he said.

Dhar told us a story about his experience in Pakistan. He was engaged in some serious discussions with the Pakistanis after the Simla Agreement. In the middle of the talks, Dhar developed laryngitis and the Pakistanis summoned a doctor to examine him. He happened to be a Bengali gentleman, who did not know much Urdu. But Dhar spoke to him in chaste Urdu and the doctor was also tempted to speak in the same language.

After examining him, the doctor told Dhar that the only way was for him to stop the bakwas. What he meant was that Dhar should give some rest to his larynx, but the word he used meant nonsense. Dhar’s comment was that this doctor was not at the talks; then how did he know that he was talking bakwas all the time?

Dhar always operated through confidants, but his confidants did not belong to one community or state. He had the gift of spotting talent and making use of it. Apart from Fotedar, he brought Gopi Arora as minister (economic), even though Peter Sinai, as the deputy chief of mission, was already entrusted with economic work. He trusted both of them and made them work as a team. He brought my batchmate P K Singh along, but put me with him to work as a team of political assistants to him. Outside the embassy, his confidant was Parayil Unnikrishnan, the PTI chief in Moscow.

To me, somehow, Dhar matched Chanakya of my imagination, tall, handsome, intelligent and stylish. But there was nothing Machiavellian about him. He appeared transparent, honest and upright. I wish I had worked with him longer.

T P Sreenivasan is a former ambassador to the United Nations, Vienna, and former governor for India, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna.

This article was originally published on rediff.com on 15 June 2005. Read the article here.