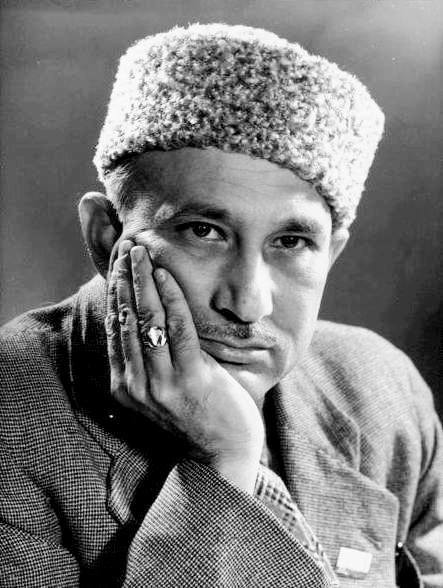

An excerpt from I Am Not An Island by Khwaja Ahmed Abbas (pages 304 – 309).

1947 – At about noon our little plane landed on the Srinagar air strip. We were met by several army trucks and a jeep which seemed to have been sent for me. It was driven by a handsome young Kashmiri who was in woollen khaki trousers, thick boots, a buttoned up jodhpur coat, a fur cap, and a warm muffler round his neck. He also carried a rifle slung over his shoulder. “I am Deepee,” he said which, at that time, meant nothing to me. But on the way to Srinagar he introduced himself more thoroughly as D.P. Dhar, one of Shaikh Abdullah’s young men who seemed to be doing a dozen things—from training Kashmiri boatmen and farmers into a militia to keeping track of the infiltrators who were still prowling about the valley, and looking after the intellectuals who were coming in every day. “There are already nearly twenty of them and the guest house number three is fairly chock-full of them. But it doesn’t matter. We will get another of the royal guest houses opened for you and those who come after you.”

Later on, I came to know that he was Lucknow-educated (which meant the slightest Kashmiri accent), was a member of the Students Federation, and a friend of Sardar Jafri about whom he made solicitous enquiries. Finally, he revealed that he was the Deputy Home Minister in Shaikh Abdullah’s Cabinet and, again, I was reminded of Spain where, young intellectuals were also drafted into ministerial positions and went about carrying rifles, at the time during the heroic (but, alas, hopeless) struggle against fascism!

“Guest house number one” proved to be a palatial affair, and the suite that was opened for me was last occupied by (if I remember right) the Maharaja of Patiala.

“But what does it matter?” D.P. told me when he unexpectedly jeeped in in the evening. “It’s a revolution. The Maharaja has run away, and the people have taken over. Come on, let me take you to the other guest house where all your writer friends are staying—then I will leave you for my other work.”

I was indiscreet enough to ask, “What is your work?”

Hunting,” he simply said, patting his rifle, “along with Bakhshi Saheb. We have heard of some raiders hiding behind the airport.”

He jeeped me through frost on the ground—it hadn’t begun to snow then to the other guest house where a dozen or more writers were gathered round the fireplace—Ramanand Sagar, (who has since become a successful film producer) who was then completing his novel about partition, Aur Insan Mar Gaya; Rajinder Singh Bedi who was collecting material for Namak, his epic story of salt, and its importance in the life of Kashmir; Mrs Chandrakiran Sonrexa who was a short story writer but was now writing a novel; Navtej Singh, the Punjabi writer of short stories and the son of the famous Punjabi writer Gurbaksh Singh of Preet Lari; Sher Singh (or was he Sher Jung?), fighter and writer, who went about in a jeep in riot-torn Delhi, shooting at sight any arsonist, rioter or would-be murderer. Raj Bans Khanna (a nephew of Balraj Sahni by marriage), an intellectual and a leftist, who was the head of the Kashmiri national militia and had taken leave from his duties to spend an evening with the writers. The atmosphere reminded one of Spain and the International Brigade where, it was said, writers had come to live their books, and poets had come to die for their poetry! The creativity of these writers was infectious and rashly I promised to read my latest story the next evening. As I walked back to my own guest house, the first snow-fall of the season was like a soft white carpet on the ground, glistening in the starlight. I decided there and then to complete a story in less the twenty-four hours and read it to my writer friends the next day. That story was Sardarji which, through a sheer misunderstanding, involved me in a court case and several adventures. But at that time these events were far off, in the womb of time. It gave me a great creative satisfaction to finish that story by the next night, and to read it to a group of appreciative friends, who all liked it very much—specially the three Sikh friends, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Navtej Singh, and Gurmeet Singh the photographer. At the end of it, a young army officer told me, “The story is very good, very effective in conveying its message of humanity. But if I were you I would not publish it for some years.” I wish I had followed his advice!

Through the courtesy of D.P. and a National Conference worker, Gandarbali, I was lucky enough to visit the Uri front which was within a mile or so of the Pakistani forward lines. On the way, we passed through Baramulla, seeing the ruins of the once prosperous town (including the chapel which was in shambles) and were shown where Maqbul Sherwani, the young and intrepid National Conference worker, was tortured and ultimately shot.

The Uri sector was then under Brigadier (later General) Sen who was most cordial and cooperative. He even sent us with some soldiers to inspect the site of a skirmish the previous night, where some Pakistani raiders’ dead bodies were still lying. There were three of them, presumably ignorant tribal people of the Frontier province and the cry of Jehad had brought them to their death in Uri. I was surprised, however, to find the Indian soldiers refer to them as “Musallahs” and not as Pakistanis! The subtlety of the correct nomenclature entirely eluded them. After all this was the war which was being waged with the help and assistance of the people of Kashmir, most of whom were Muslims and, thanks to their leader, the redoubtable Shaikh Abdullah, anti-Pakistanis.

This was the war in which, only a few miles away, a Muslim called Maqbul Sherwani rather died than give up his secular and pro-Indian attitude.

I took up the matter with Brigadier Sen and he expressed his helplessness in the matter. He said in effect, “It is difficult to change the thinking of these soldiers who are ignorant of the principles of secularism.” I wanted to ask him: then what is this war about? What am I, a “Musallah,” doing here? But I preferred to keep my mouth shut, making a mental note fit for reference to Jawaharlal Nehru, if and when I got a chance to discuss the matter with him.

We had our lunch in an orchard where apples hung invitingly low, and just then, we were presumably, sighted by the Pakistanis through their field glasses for two mortar shells fell dangerously close to us. This was real war, and we could have all died there and then, as Brigadier Usman was to die in another sector–the most important Muslim to lay down his life for secularism and Kashmir. Yet, I was not afraid of death in that moment. Was it because of the company I had—Marg-e-Amboh jashn na darad (When you die in a group, there is no celebration!)—or was it some sort of contagion of bravery? Anyway, when we returned to Srinagar along the hairpin bends of the serpentine hill road, we left the war behind. The danger of our jeep falling down the khud was more imminent and frightening than any Pakistani mortar shells could be!

That night or, maybe, a few nights later, I and D.P. discussed the chances of winning the plebiscite—if there was one. D.P. asked me what did I think of the chances? I told him the climate of Srinagar at that time was definitely against Pakistan. I had talked to Kashmiri craftsmen, boatmen, paddy farmers, porters—almost all of them Muslims—and they all had unpleasant experiences of the raiders who were uncouth fanatics who knew nothing. I could personally vouchsafe for this, for I had met a raider in Srinagar jail who could not read or write or articulate except to say that he was sent to save the Kashmiri Muslims from the tyranny of the Maharajah. When I told him that there was no Maharajah and the “big man” in Srinagar was Shaikh Abdullah, he remained silent and sullen. Evidently, he had not heard of the Shaikh Saheb’s name.

“If there is going to be a plebiscite—and I find Panditji had committed himself to it before the international public opinion—India should hold it within a month.” This was an opinion which I could express between friends. “Let India fix the date soon and give an ultimatum to Pakistan to clear out of the occupied territory—if they don’t, they will be responsible for the consequences. India would hold the plebiscite wherever its writ runs—and then declare the results to the world. I don’t think we can go wrong, provided we work fast and don’t allow the ‘Islam in Danger’ cry to be raised!”

D.P. said thoughtfully, “You know, Khwaja Saheb, many of us here are also thinking along the same lines. Will you discuss it with Shaikh Saheb and, if he agrees, will you go to Delhi to suggest it to Panditji?”

I was afraid of Panditji, but willing to stick my neck out, and I said as much.

D.P. fixed the appointment with Shaikh Saheb the next day. Shaikh Abdullah was surrounded by a big Durbar-farmers, and boatmen, fishermen, craftsmen, everyone could walk into his house, without much ceremony. He had known his people since the days he was a school teacher, and they knew him, and there was a democratic rapport between them. He was a five times-a-day praying Muslim and that gave him a solid base for his leadership. The Kashmiri Muslim is essentially religious, and it was a miracle that Shaikh Abdullah had persuaded them that their salvation lay in working together with their Hindu compatriots, and so he had converted them to secularism, turning his original Muslim Conference into a National Conference.

“Who came to our help in the time of need, defying the power of the maharajah?” he would ask in his orations after Friday prayers.

The people would reply in chorus, “Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru!”

And Shaikh Abdullah would drive the shaft home by saying, “Not Jinnah Saheb, who was too busy hobnobbing with the maharajas and nawabs.”

The Shaikh was a simple man, simply dressed in the style of the upper middle class Kashmiris, and he spoke to the people in Kashmiri, their own language. It was obvious that they loved him and adored him.

When I came in, he excused himself and led me on to a verandah which was flooded with the cold-weather sunlight.

“I am glad you have come again, Khwaja Saheb,” he said, referring to my earlier visit when he was in jail. “I suppose we can give you slightly better hospitality.”

“Khwaja Saheb has some suggestion regarding the plebiscite,” said D.P., afraid that our talk would drift into a series of polite exchanges.

“Yes?” Shaikh Saheb gave me the cue. Then he heard me patiently as I proposed my theory about an early plebiscite. “I feel that now is the time when the whole valley is reverberating with Humla-awar khabardar—Hum Kashmiri hain tayyaar! that the plebiscite should be held. It should not be postponed.”

“I will not say yes. And I won’t say no. Panditji must have his own reasons for delaying the plebiscite. It is better to discuss it with him first. Though you have made a plausible point, I will only do what my leader says.”