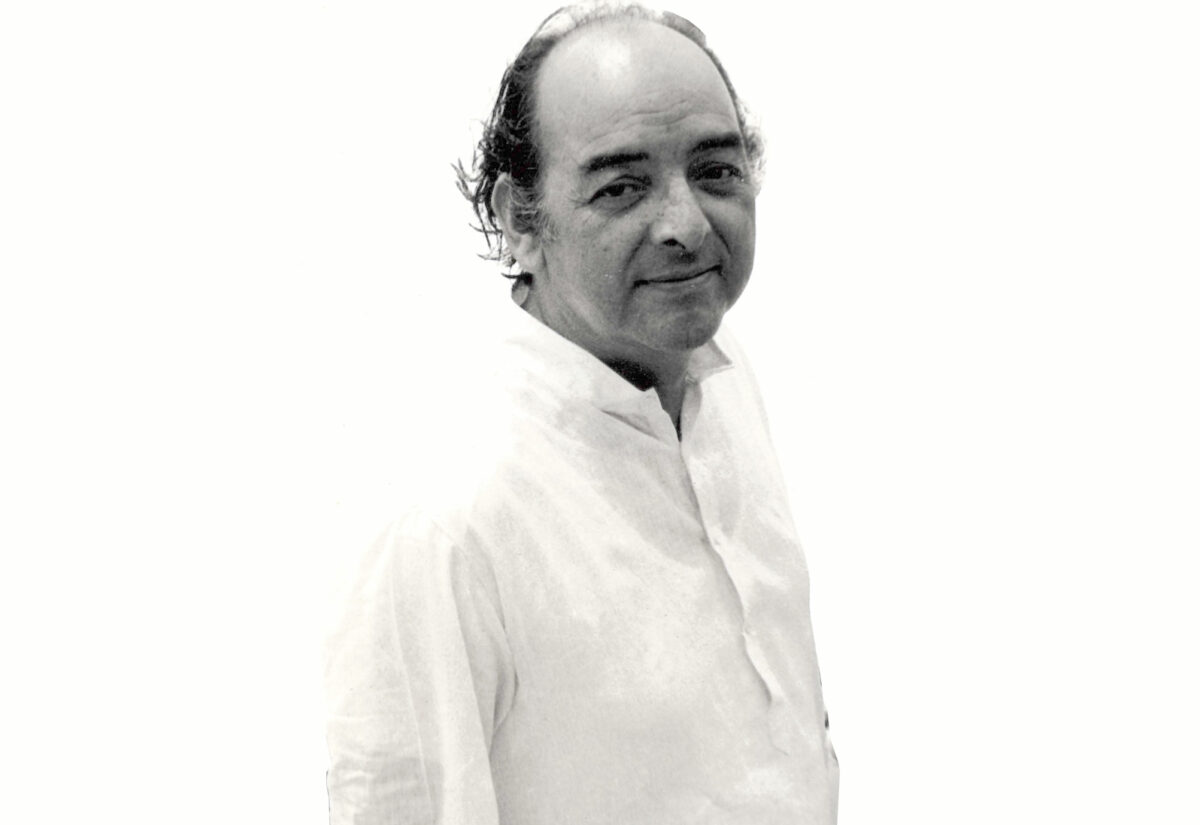

EVERYONE, but everyone—young or old, friend or stranger, rich or poor, admirer or adversary—called him D.P. though there was a solitary and significant exception. Jawaharlal Nehru alone addressed him as Durga but never as Durga Prashad, the full name fond parents had given the late D.P. Dhar.

A year after his tragic and untimely death—he was still in his mid-fifties—the pain persists. The passage of time has done nothing to blur one’s memories of him. On the contrary, these are sharper which, by itself, is an eloquent tribute to Dhar. For, in politics, even a fortnight is a long time. Of how many politicians, who once occupied the centre of the stage even more prominently than D.P. did, can it be said that they were, or are likely to be, remembered so intensely 12 months after their demise?

Restless

Indeed, being in or out of power had very little to do with the niche D.P. had made in the hearts of many people or with his distinctiveness as both an individual and a politician. For six years, from 1958 to 1964, he, along with G. M. Sadiq, Mir Qasim and some others, was out in the political wilderness while Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed ruled Jammu and Kashmir with an iron hand and, on the side, took an occasional swipe at comrades turned critics. But throughout this period, neither in Srinagar nor in New Delhi, did D.P. give the impression even for a moment of being deflated or depressed. He carried himself with the same zest and aplomb that he displayed at the height of power and glory. Restless he would be, whether in office or not, but out of sorts, never.

To me, as to countless others, the quality that set D.P. apart from most politicians of his generation was his extraordinary graciousness. He was in the business of politics for the sake of power, no doubt, and nothing delighted him more than being able to manipulate the levers of power from behind the scene and yet be seen to be doing it. In pursuit of his objectives, he could be ruthless, remorseless and even devious. But no matter what he did, he did it with exquisite grace and charm. He was courteous to the point of being courtly and seldom failed to employ the weapon of subtle flattery if it suited his purpose. It was the human warmth behind every gesture he made, however, that bowled over whoever came into contact with him. I know of no one else who could come two hours late for an appointment and apologise with such finesse and profusion as to make the irate host feel ashamed of himself.

A merciful providence had blessed him with exceptionally good looks. Along with equally exceptional ability, polish and eloquence this made for a formidable combination. His refinement was so captivating because it was so rare; his charm so over-whelming as to be deadly. At least one woman of luminous beauty once candidly told me that she found D.P.’s charm irresistible.

The point may be trivial, but it is worth making: D.P. managed to look equally elegant in a Saville Row suit or a loose kurta- pyjama. As a host, he had few equals. Not only was he generous to a fault but, being a gourmet himself, he recognised kindred souls when he saw them and took pains to ensure that the cuisine served to them con¬formed to his own impeccable taste. Add to this his sparkling conversation, enlivened further by ample libations of Scotch, and it should be clear why an evening spent with D.P. was always an unforgettable experi¬ence. Here was a host whose sophistication of mind matched his superb manners.

An illustration of D.P Dhar.

Were this all that is to be said of him, D.P. would have been too good to be true. But there was, alas, another side to the man which flawed his fine personality considerably. It is not easy to pin down precisely what was wrong. But it is a pity that even at his best D.P. failed to be wholly convincing. An impression lingered as if he was pulling a fast one. As if he had something up his sleeve which he was successfully and gleefully hiding. A few even began to feel that his charm, too, was synthetic. Towards the end, the most frequently heard jibe against him was that he was relying not so much on policy as on PR.

Loved by Many, Trusted by Few

Yet the surprise is not that there were people who disliked or detested him but that their number was so small. By comparison, the number of those who liked and loved him was legion. But the irony of it all is that even among his ardent admirers those who trusted him fully constituted only a tiny minority. How tragic can be the consequences of even minor flaws in the make-up of the finest of men!

To lay undue emphasis on this point, however, will be a mistake on a par with judging Panditji by what he did or failed to do in the last two years of his life rather than by the totality of his achievements and failures. Viewed as a whole, D.P.’s record is a glittering one. Since his career has been far too well known it will be a waste of time and space to recount it. A few highlights should suffice.

In the first place, he was not a politician of the usual Congress school at all. Nor was he a man of the masses. He did not sway crowds by his oratory. But in a committee or party caucus he was as superb as round a negotiating table. Few people have used either the state apparatus or the party machine as skillfully as he did.

Secondly, both power and fame came to him at a very early age. He was in his late twenties when, in the wake of freedom and partition, came the Pakistani invasion of Kashmir. As he was to do on countless occasions later, D.P. plunged headlong into the crisis, enjoying every moment of the great but risky adventure. His taste for dramatic gestures and penchant for rushing in w h e r e his peers and even seniors would fear to tread were thus developed during his formative years.

The way, on first hearing of the Pakistani paramilitary infiltrations into Kashmir in August 1965, he dashed off to the danger- spot has by now been recorded by many including Banchi Mangat Rai, then Chief Secretary of Jammu and Kashmir, who was quite used to receiving “Dear C.S.—Love, D.P.” notes.

Later, I was witness to some even greater feats of daring which are not yet a matter of public record. Before the Pakistani infiltrators received their just deserts, there was an awkward moment when they seemed in a position to take over the Srinagar airport. The army, quite properly, had refused to join anti-infiltrator operations, keeping itself in readiness to meet the military challenge.

But the Divisional Commander in the vicinity of Srinagar took his instructions a trifle too literally and declined to do anything when a perceptive civilian officer asked for help, to save the airport.

D.P. it was who, at the dead of night, rushed off not only to the airport but also to the bunker of the Major-General to persuade him to see reason and redeploy some tank formations! A few days later still, D.P. put on the fire brigade uniform to dash off to the Batmalu area of the city to fight the notorious fire started by Pakistani raiders.

When the full-fledged war in the plains of Punjab started in 1965, I could not help being impressed by D.P.’s deep personal rapport with the senior military leaders. The reason for this turned out to be simple. During the 1948 war in Kashmir there was hardly a major or colonel with whom D.P. hadn’t shared the hardships of the battlefield. These officers had by now risen to be divisional or corps commanders.

In the Tithwal sector in 1948, D.P. and a bright young lieutenant-colonel had walked for days, fording rivers and climbing mountains, nearly losing their toes due to frostbite. In 1965, the colonel had become Lieutenant-General and commanded the entire front from Kargil to Kutch. His name: Harbaksh Singh.

By 1971 Harbaksh had retired from the army but D.P. was still going strong. That year and the next was, without doubt, the highest point of D.P.’s career, what with his skilful negotiation of the Indo-Soviet Treaty and superb handling of all aspects of the Bangladesh crisis. Long before the Americans moved the Seventh Fleet he was warning the military top brass that they must remember American landings at Inchon in Korea. No wonder people talked of him as India’s Kissinger and General (later Field- Marshal) Manekshaw hailed him as “My Political Commissar”.

The peak was reached perhaps when, reciting Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s superlative verses to Pakistan’s Aziz Ahmed at Murree, D.P. paved the way to the Simla summit. At Simla, however, he fell ill at a crucial moment and his downhill journey began.

Planning Was Not His Cup of Tea

There are a great many Central Minis-tries that D.P. could have presided over with distinction as a member of Indira Gandhi’s Cabinet. But, for reasons which still remain obscure, she assigned him to Planning. A more unfortunate choice could not have been made. At Yojana Bhavan, already a graveyard of many political reputations, D.P, was wholly out of his depth. In the words of one of his official advisers, quoted by M. Chalapathi Rau, D.P. tried to please all Chief Ministers with promises he was in no position to keep. And soon the jig was up.

D.P. went to the Embassy in Moscow for a second stint much against his will. Within a few months, he was dead. He may well have died as much of a broken heart as of a heart attack. But there was another reason for the unhappy and unexpected end: his consistently poor health. But for this, he could surely have returned from the Soviet Union to better things and to fulfil his pro- mise to the fullest. That, also, was not to be because D.P.’s weakness for drink had played havoc with his physique.

Under doctor’s orders, he had to give up drinking repeatedly but repeatedly did he return to the bottle, usually to hit it rather hard. One of my most poignant memories of D.P. is of an evening in Delhi when both he and the late Frank Moraes—another ardent devotee of Bacchus, but then recovering from cirrhosis of the liver—sat facing each other and nursing glasses of fruit juice at a dinner party.

How ironic it is, therefore, that when D.P. was first appointed Ambassador to Moscow in 1967, it was Frank who wrote that the assignment would put to the test his capacities “for both drinking and diplomacy”.

In a long career of political reporting, I have got to know many men of politics rather well, in some cases intimately. But the number of those politicians who can even remotely compare with D.P. in charm, graciousness and warmth can be counted on the fingers of a badly mutilated hand. Of those in this category who are still with us, either in active public life or retirement, I will say nothing. But I have no hesitation in mentioning the names of the two men in the same class who are no more: Feroze Gandhi and Nath Pai.