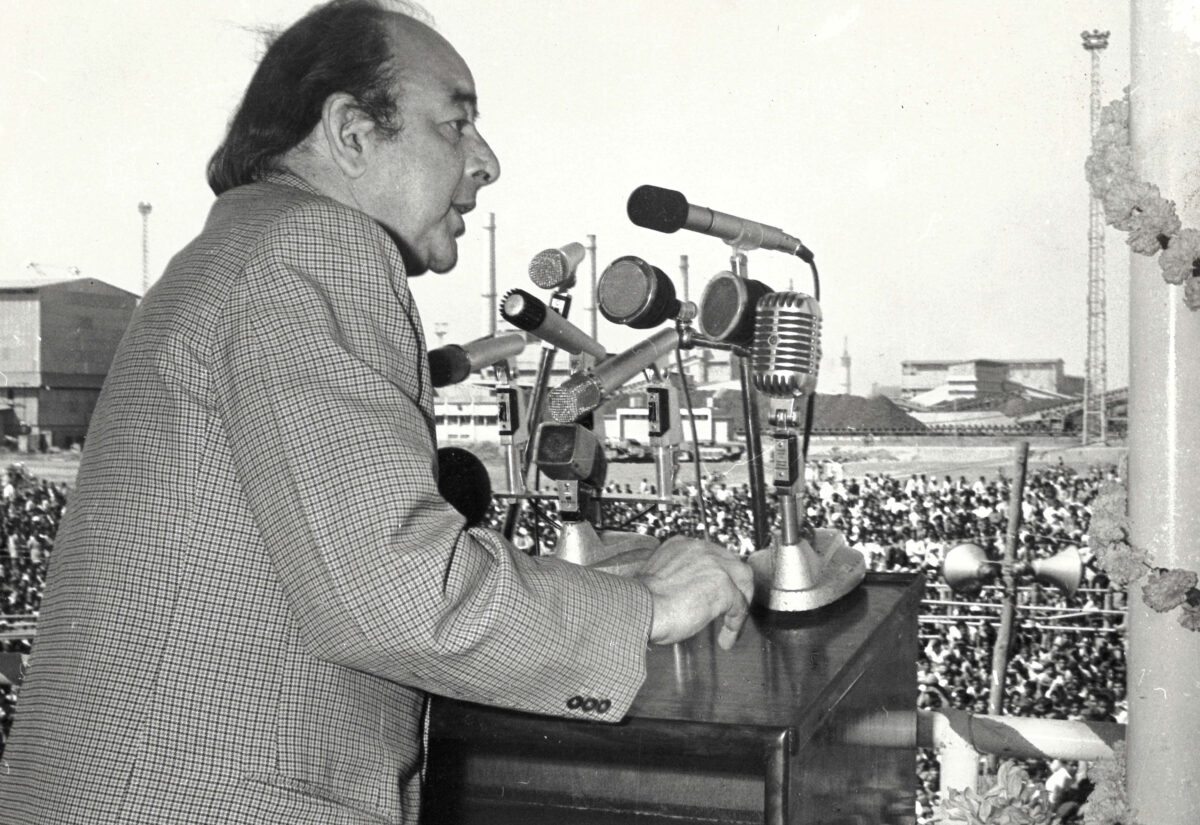

This speech, delivered at the National Defence College in November, 1972, barely a few months after I took charge at the Planning Commission, deals with the political complexion of the independence struggle and its impact on our development effort. It goes on to identify the political and social basis for the two objectives underlying the Draft Fifth Plan-poverty removal and self-reliance.

It is somewhat difficult for those of us who grew up after independence to realise the significance of the fundamental debates that went on, even while the freedom battle was being fought, about the pattern of economic and social development of independent India. It was in the course of these debates that Jawaharlal Nehru placed before the country a clear vision of a modern industrial society, based on science and technology, which would ensure for all citizens of India opportunities for the fullest material, intellectual and spiritual growth. Such a society, in his conception, was to be built not by following the path of capitalist development but by a conscious departure from the models of development that had been followed in what are today’s advanced nations.

The whole history of the Congress, and indeed the whole history of the tremendous political, social and intellectual ferment that characterised India’s response to the colonial domination, is in one sense a battle for supremacy between two forces. On the one hand there were people who thought that India could best develop her strength by adhering, in the main, to the principles of what has come to be known as the free enterprise system. Under the umbrella of British colonialism, there had grown a weak middle class, based largely on merchant capital, which after some false starts, had cast itself in the role of its historical predecessors in the West. Accordingly, the political forces represented by the nascent industrial and commercial class saw the future of independent India as one of traversing the path that had been trodden by the advanced Western societies. Undoubtedly, in this class there were elements that failed to appreciate the basic contradiction between the existence of feudal relations in land and the growth of a modern industrial society based on capital accumulation by the middle classes. This led to the curious paradox of Indian capitalism, such as it was in the pre-independence days, marching hand in hand with a bankrupt feudalism. Some of these contradictions can be explained by the presence of alien rule, but the fact remains that on its own the Indian middle class failed to carry through, even in intellectual terms, the kind of thorough going change that had occurred in the West. In essence, therefore, the Indian bourgeoisie was something of a caricature of the vigorous, full-blooded, ruthless and innovative bourgeoisie of the West to whom Marx had paid such a magnificent tribute in the communist manifesto. In short, it was merely a pretender, and not a real claimant, to the role of the leader of India’s economic regeneration. But its members were articulate, even though their ideas were borrowed; its capacity for monopolising forms and techniques of political action was considerable, even though the broad masses could neither understand its idiom nor be enthused by the vision of society it portrayed. Because of its early advent into politics it continued to dominate the economic debate for a long time.

The other force was represented by the victims of British colonialism, the hapless peasant, the working class which modern industry and the halting application of science and technology had brought into existence, the intelligentsia which modern education produced but for which the social and economic system did not have much use, and the growing army of the unemployed, both in the rural and the urban areas. In their own confused way these forces had sought entrance into the national movement through isolated actions. There were peasant struggles against the landlords; there were strikes by the workers; there was terrorism by the educated youth. But even after Gandhi had broadened the base of the national movement by bringing the vast peasant masses into the forefront of our political struggle, there was no comprehensive framework of political and economic ideology that would bind various classes in a common endeavour to solve the fundamental problems of Indian society. The broad anti-imperialist front that Gandhi forged could not be sustained for long on the basis of a combination of values and ideologies that ranged all the way from pure traditionalism, including varnashram dharma, to modern economic development through large-scale industrialisation.

The incongruity of this mixture was to act, time and again, as a brake on the progress of India. It was left to Nehru to stand out as an uncompromising champion of a new synthesis, a synthesis that took fully into account the historical achievements of the industrialisation process in the West as also of the path of socialist modernisation of a backward country like Russia.

In working out his blueprint for India’s modernisation, Nehru did not think in doctrinaire terms, though in the late twenties and thirties his young and sensitive mind was powerfully attracted by the Russian Revolution.

He conceived a comprehensive strategy for India’s advancement. To his mind, the structural characteristics of a colonial economy and the complete transformation of the world scene, consequent upon the two great world wars, ruled out the possibility of India. achieving social and economic modernisation through processes inherent in a system of free competition. Not only have the growth of modern technology, both industrial and military, rendered the concept somewhat obsolete even in countries which continue to swear by it, but the cure of agricultural and industrial backwardness of colonial economies was contingent on a categorical repudiation of the system of free competition in order to enable the State to carry out fundamental changes in economic and social relationships. Feudalism had to go, and the peasant had to be given a right to the land he tilled. The pattern of international trade, which condemned the backward economies to remain exporters of raw materials and importers. of manufactured goods, had to be ended in order to ensure. for the common people a higher standard of living. This could be done only by laying the basis for industrialisation, namely, by creating machines that create machines. These changes could not be brought about without mobilising on an unprecedented scale the entire human and material resources of the community. These were not things that could be done, or even attempted to be done, within the framework of feudal relations in agriculture and of capitalist relations in industry. The worker and the peasant had to have a central place in the whole scheme of things before the slow and painful process of modernisation in India could begin. Therefore, Nehru struggled, at the head of the newly awakening forces in the countryside and in the cities, to win acceptance for a socialist model of development. I have tried to paint, in bold strokes, the fundamental lines of debate in pre-independent India because it is only an understanding of the issues that were posed at that time and of the manner in which they were resolved that can enable us to appreciate our present situation.

Today’s India, which has witnessed an agricultural revolution, which has built basic industries and has enormously expanded the range of manufactured goods that are produced within the country, and which has so modernised its defence forces as to face successfully military aggression twice in a matter of six years, is a product of Nehru’s vision. The two combating ideologies, of which I spoke earlier, may now seem to be commonplaces of thought in so far as India is concerned. But it is worth remembering that although the process of planning began in 1952 it was not until 1957 that the socialist pattern of society was fully accepted as the basic objective of economic development and was explicitly mentioned in the Second Five Year Plan document. The second five-year plan may, then, be seen as the culmination of a long process of confrontation between two opposed systems of thought, between two opposed strategies of development, and between two basically antagonistic conceptions of the social order, in which eventually the forces represented by Nehru gained ascendancy. The pattern of development that we have followed since, the strategic aims that we have placed before ourselves, and the instruments that we have employed to achieve those aims, can now be seen as a logical outcome of that struggle. Therefore, when I talk to you today about the economic strategy for the seventies, you would do well to bear in mind this historical perspective. It is necessary to do so not only because there is no better way of honouring Nehru than that of re-capturing in our lives and in our actions the freshness of his vision, but also because the problems we face today bear an integral relationship to his vision. In the twenty-five years since independence, India may not have climbed out of its backwardness, but it has made purposeful strides towards modernity. Today we are dealing only partly with the problems of making people move. Very largely we have to deal with the problems of providing the wherewithal for people who have moved and wish to move faster. The tensions and the conflicts. in our society today are the tensions and conflicts which growth has brought into being. To this extent, and to this extent only, we have proved ourselves worthy of his legacy. But the modern India that is emerging before our eyes out of the shadows of the past confronts once again a directional chaos.

I will not take your time by a detailed recital of the gains which have accrued to us as a result of pursuing the strategy of planned development. These are impressive enough by any historical standards, even though in our impatience we are inclined to ridicule the rate of growth of our economy since independence. It would restore a sense of historical perspective to remember that the Western economies in their formative period of growth grew at something like 1. 8 per cent annually. The per capita annual growth rate for Britain and France was only 1. 2 to 1. 4 per cent. Even in socialist countries, the growth rate was around 4 per cent or slightly above. Therefore, the Indian experience of an average rate of growth of about 3. 5 per cent is not something to be scoffed at. Shifting attention from the growth rate for a moment, we can see that an economy which increases agricultural production from something like 45 million tons in 1949-50 to over 100 million tons in 1970-71 is an economy that is moving forward at a tremendous pace. Similarly, the index of industrial production shows that between 1951 and 1968 India’s industrial production increased by 194 per cent. I could also cite the tremendous expansion of enrolment in educational institutions, of facilities for medical care, of communications, etc. But I hope I have made my point, namely, that looked at in the historical perspective the Indian experiment in planned development, starting largely with the Second Five Year Plan, has significant achievements to its credit. I am not one of those who gloss over our weaknesses, to which I shall return presently. But equally, I have been unable to sympathise with the point of view which looks upon the Indian experiment as one long and dismal story of failure. Our young officers have particularly to grasp this fact, not merely in an intellectual fashion, but as something that is living, something that is a vital presence in the fabric of our national existence. A corrosive cynicism and a spirit of defeat seem to take hold of our minds at the slightest suggestion of imbalances and difficulties in the economy. This way no country, no society can grow. It is only for this reason that I have endeavoured to place before you certain facts, certain telling facts, which bear comparison with what has been achieved by other societies in similar phases of their development. This is the basis of my confidence, not any mantram about the glory of our heritage, not any vague sentimental belief in the beneficent effects of our strategy, but solid incontrovertible results of our path of development are the basis of optimism regarding what we can achieve in the seventies.

At this point, I would like to introduce for your consideration another aspect which has crucial significance for the whole strategy of growth in the seventies. You may recall that when we started our experiment of the comprehensive development of our national economy the international scene was vastly different from what it is today. The fifties and the major part of the sixties were characterised by the cold war. Two superpowers armed with nuclear technology confronted each other, and the world was an arena in which the competing goals of foreign policies of the two powers absorbed the energies and efforts of a large number of nations. In this difficult period, India chose to pursue a policy of nonalignment with the objective of promoting peace throughout a tension-ridden world. Since we were not militarily aligned with any superpower, we did not expect to be made a battleground to resolve issues of global strategy which convulsed the nations forming part of one or the other bloc. In 1962, however, our assumption that we could pursue growth and development in comparative security was shattered by the Chinese. We realised that in order to develop economically we bad at the same time to be militarily strong.

Now a modern defence system is not just a matter of acquiring equipment and weapons, as you gentlemen know very well. It is first and foremost a matter of developing rapidly a modern scientific and technological base, of developing a sophisticated industrial system which can provide to the defence forces what they need in terms of equipment, etc., and of a dynamic economy that can bear the burden of colossal investments required for growth in agriculture and in industry, together with the vast expenditure required for recruiting, training, and maintaining a large, modern defence force based on complex weapon systems. In this context, a relatively long period of peace would have given us the time needed to develop, from out of our own resources, means for undertaking large scale modernisation of our defence forces without having to depend on external powers for assistance. But such was not the case. The deliberate arming of our neighbour by the Western powers, which would have consequences that were foreseen by Nehru, inexorably pushed us into strengthening our defence forces with the objective of maintaining an overwhelming defence capability. This, however, meant a large scale diversion of resources that were badly needed at that stage for investment in the growth sectors of economy. What I am trying to drive at is that whereas in mature capitalist economies of the West, production of armaments, for actual or potential use, now serves to promote overall growth of their economies, in developing countries the whole pattern of the international arms economy introduces a distortion that cannot but come in the way of rapid development. The Western economies would face serious crises without heavy governmental expenditure on manufacture of armaments. But having once manufactured them, they cannot use all of them themselves. Therefore, they must promote similar patterns elsewhere. If they arm Pakistan, India is forced to arm herself. If America arms South Vietnam, it forces North Vietnam to acquire matching weapons. Thus the rat race goes on and the developing world as a whole faces the unpleasant choice of either surrendering its political freedom or of acquiring arms by spending free foreign exchange which means less of resources available for productive investment.

The straitjacket which the developed world, particularly the developed world of capitalist economies, has caused to envelop the developing countries imposes new strains on us. These strains were somewhat eased during the period of the cold war by the willingness of the Western countries to offer large amounts of assistance to the developing countries for strengthening the productive capacities of their economies. In the particularly difficult international situation we found ourselves at that time, there were not many options, and we accepted a good deal of foreign assistance for financing our investments in industry and in agriculture. Our burden was eased, but only temporarily, because very soon the burden of repaying the debts and of the interest thereon began to grow. In the meantime, political developments in the international field have brought about new realignments, a new configuration of world forces. The cold war belongs to history. Yesterday’s adversaries now clink glasses together. They are entering into wide-ranging trade agreements, providing much-needed relief to their economies overheated by two decades of frantic arms building. Even China has emerged out of its long isolation and is looking eagerly at the West for such crumbs of comfort as may fall from the richly laden plates of the mature economies. As the tensions of the cold war disappeared, the compulsions, political and economic, which promoted large scale assistance by industrially developed countries to the less developed countries would also lose their power. It has already begun to happen to a large extent. The net flow -0f aid to developing countries has declined sharply in the last three or four years, and there are no signs that its level would rise to anything like one per cent of the gross national product of the developed world which the World Bank Team under Lester Pearson had postulated as a desirable target. Not only will the magnitude of aid decline progressively, but what is more to the point, the net burden of foreign debts that our economy carries will grow from year to year, thus reducing our capacity to buy goods and services in the foreign markets for the purpose of developing our economy.

At the same time the objective realities of the international situation, including the attitudes and motivations of the rulers of the countries in our immediate neighbourhood, leave us no option but to place our defence forces at progressively higher levels of preparedness in terms of technology and the weapon systems. As an old proverb has it, it is no use building a beautiful garden without building a strong fence to keep hefty cattle away. I have referred to the dramatic changes in the international situation only to emphasise that the dimension of self-reliance, which has formed part of our thinking on the strategy of development, must now receive overriding priority. The seventies are going to be a period in which the comfortable assumptions of planners. in the sixties regarding availability of foreign aid would become increasingly untenable. Even if it were not so, one would be inclined to doubt the wisdom of relying on foreign aid to speed up the process of growth in our country. We can now see that a large portion of our production is earmarked to pay for what we borrowed in the past. It is as much as. 30 per cent of our entire exports. To borrow more now means placing our future gains in jeopardy. The ideological battle for the soul of the third world having ended, the soul finds itself left out in the cold. It is not necessarily a bad thing. Out of our present predicament will emerge the new directions of effort to realise the dream of setting ourselves free from our economic bondage. Many years ago Jawaharlal Nehru at the First Asian Congress in Delhi spoke of the end of an era when Asian and African nations waited upon their masters in the courts and chanceries of Western nations. The political domination ended in 1947, but we had to continue to woo the bankers, the captains of industry, and the masters of technology of the West. They wore a benevolent face, and they spoke a new language of helping the poor and the backward. But their motives had not changed. Only their style had. Instead of overwhelming us with their armies, they overwhelmed with the kindness of their crushing debts. Now when we are in a position, with a little extra effort, to stand on our own feet, they no longer use kind and sweet words. They insist on their pound of our flesh. This, then, is, in stark terms, the situation we face. Self-reliance becomes, therefore, not a matter of slogans, as some learned people in their infinite wisdom are apt to imagine, but an obligation of survival as a free people. From this imperative alone can any strategy of growth in the seventies be fashioned.

I would like to invite your attention to a historical parallel, even though it is not similar in all respects. You are no doubt aware of the circumstances attending the Russian Revolution, the civil war and the active involvement of the Western powers in the civil war against the revolutionary regime, the threat to the survival of the Russian Revolution and the prolonged period of hostility on the part of the West towards the new regime. Now in this historical situation the theoretical assumption of the success of the Soviet Revolution being dependent on revolutions in other industrialised countries, particularly Germany and England, was seriously questioned by the Russian leaders. The objective reality of the situation was that a revolution had not taken place in Germany nor was it likely to take place. Similarly, the enfranchisement of the working classes and the formation of a political party representing the working classes had determined for England a path of national development which was not in keeping with the implications of the orthodox Marxist model. What did the Russians leaders do? Flying in the face of dogma, they proclaimed the slogan of ‘socialism in one country’ and proceeded to develop the strength of the Soviet State in accordance with the priorities forced upon them by the then-existing international situation. I have chosen to refer to this historical example only to show that national development is not an autonomous progression of events uninfluenced by the framework of international relations. It is not without significance that it is only in the socialist countries today that we find a sympathetic understanding of our striving for self-reliance, because from their historical experience they know the dangers of dependence on outside forces for purposes of development.

To bring together the threads of my argument, it is necessary now to give you a synoptic look at the fundamental features of our economy as it exists today. Having accepted Nehru’s design for our economic development, in the course of three Plans-the first one was basically a plan of consolidation rather than of any significant advance-we have taken important steps towards modernising our agriculture, creating a technologically complex infrastructure for industrial and agricultural growth, building a number of basic industries which provide a continuing stimulus to further industrialisation and widening the range of goods and services available to the common people. However, many of the weaknesses that we inherited from the past remain with us. First, even though we ended in the fifties the feudal relations in land, the next step of redistribution of land to the actual tillers and to the landless was not taken. The result was that in large parts of the country a system of production was established which offered no incentives to the tenant and to the agricultural labourers for raising productivity. It was apparent that the gains resulting from increased productivity would be largely swallowed by the landlord class. The new technologies of production, based on new varieties of seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, multiple cropping and all the rest of it created an imbalance in the sense that while they gave a big push to capitalist farming based on large landholdings and on growing mechanisation, the overwhelming majority of small farmers remained untouched by the innovations in agriculture, either because the existing land laws did not encourage investment on the part of the tenant or because the small landholder was not in a position to take risks with the large investment that the new technologies involved. Thus we find that pockets of high productivity and affluence coexist with a multitude of small farms where primitive technology and subsistence farming remain the cardinal features of agricultural economy. In addition, Indian agriculture still remains to a very large extent a gamble on the rains. Only about 25 per cent of the cultivable area is irrigated. Moreover, the inputs of modern agriculture are in short supply. As I have said earlier the crisis now in agricultural economy is not that of stagnation in technology. The problem is that people want more fertilisers, more pesticides, more power, more water and better seeds. Today we are not in a position to meet these growing needs. Thus, on the one hand, the existing distribution of the means of production inhibits growth of modern productive forces in agriculture, on the other where such forces have already yielded impressive results, their further growth is hampered by the insufficiency of modern inputs.

In industry, our problems stem from a comparative neglect of basic industries, namely steel, power, oil, heavy chemicals, petro-chemicals and non-ferrous metals. No doubt we have established considerable capacities in many of these fields, but partly on account of the long learning process ineffective management of these industries, and partly because of a somewhat timid approach to expansion and creation of new capacities in these fields resulting from the difficulties we faced after our conflict with China, we are today producing much less steel, much less power, much less fertiliser and much less oil than we need. At one time people thought that we were wasting money on these gigantic projects. They thought that this was a disease which had to be cured by much larger investment in agriculture and consumer industries. Today we can see for ourselves that a medicine for promoting good health was given up because it had apparently been prescribed by people who believe that socialism in this country can only be built by establishing basic industries which alone can generate resources for rapid industrial and agricultural growth. Today we are spending enormous amounts of foreign exchange for importing these very things because without them neither industry nor agriculture can move. Therefore, this entirely barren controversy relating to light and consumer industry versus basic industry should now be consigned to the dustbin of history. Experience has taught us the soundness of Nehru’s vision. The structural weakness of the Indian economy today resides primarily in the relative stagnation in the growth of basic industries. We are likely to produce by the end of the fourth plan only 5. 60 million tons of steel, whereas Japan was producing over 36 million tons in 1964, having started with only 1. 7 million tons in 1948. Today it is producing close to 100 million tons. This illustrates dramatically the gap between a backward and a modern economy.

There is another weakness to which it is necessary to refer in some detail because for some time now it has been the focal point of controversy in development economics. It is often said, and with justification, that the pattern of development in the backward countries has led to a widening of the gap between the rich and the poor. In fact, on the basis of some calculations, it has been asserted that in India after two decades of development the absolute number of people below the poverty line is anywhere between two fifths and one half of the entire population. In other words, the benefits of growth have not been equitably distributed. This means, so the argument runs, that our whole strategy of growth is lopsided. In any event there can be no meaning in a process whereby goods and services multiply, enriching a small class, while the majority continues to suffer deprivation, and even lack of essential necessities of life. Thus what is needed is to take bold steps to redistribute incomes during the course of growth itself rather than wait for a hypothetical future when there would be plenty to go round for each and every one. Ever since Myrdal in his Asian Drama drew attention to the inequalities in income between different strata of society in developing countries, economists and political thinkers have focused attention on mass poverty, with its key symptom of unemployment, as the most prominent indicator of the failure of development strategies which had leaned heavily on creating the fundamental bases of industrialisation. Now as statistics go, the distribution of income in India is highly skewed. It is also true that there is a great deal of unemployment both in the urban and the rural areas. The problem of the educated unemployed has assumed serious proportions. Should these facts be regarded as conclusive evidence of failure of the development strategy which was elaborated in the earlier Plans? Let me tell you straightaway that reduction of inequality in income and wealth was always one of the major objectives of development efforts in India. The second plan categorically made this one of its principal objectives. Therefore, it is not correct to say that the development strategy assumed that a fast rate of growth of national income would automatically produce higher living standards for the poor. Even if we were to concentrate entirely on agricultural development, and on building consumer industries, we would have sooner or later come up against those very factors which, in . the ultimate analysis, determine whether an economy would move forward or would remain stationary. These factors are related to the nature of modern technology, and the size and the scale of investment that modern technology requires. The harsh fact of the matter is that in the initial period of growth we have to save a large proportion of the increases in national income for the purpose of investing it in industries that produce capital goods. Therefore, whatever be the strategy of development that you adopt, ways have to be found to induce, persuade, or where persuasion and inducement fail, to force people to save more. This really means that for a certain period when you are building the basis for future growth, no appreciable rise in consumption standards of the majority of the people can be thought of. In India, we have not adopted drastic methods for capital accumulation. In fact, the rise in agricultural production has brought about an improvement in the living standards of the poorest among us. If only we would trust the evidence of our eyes we would see that most people are consuming sugar and wheat, and some machine-made goods which were outside the reach of a large proportion of our masses, especially in the rural areas, only 10 to 15 years ago. Even though evidence for a gradual amelioration of the conditions of living of our people is irrefutable, there is no sense in refusing to face the logic of the development process. It has its costs, its burdens. The experts from the developed world who are bemoaning the fate of our poverty-stricken people, have not paid the same diligent attention to the methods of capital accumulation in their own societies in the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. Therefore, we have to accept the proposition that if the country has to grow fast, if it has to build those industries which would place within our grasp the avenues of rapid industrialisation, we have to be prepared for a period in which the private consumption standards of most of our people will not rise in any significant way, because a large part of additions to national income in each year will have to be ploughed back into investment. The success of the strategy depends on applying this yardstick to all classes and not merely to the poor. Where we have failed is in restraining the consumption standards of the elite, which has in fact distorted our pattern of production, has led to a large import bill and has added to the political tensions in the rural and urban areas. It is in this perspective that a realistic strategy for growth has to be framed. We cannot avoid the inconvenient questions of income redistribution and of employment generation. But we cannot promise at the same time that something dramatic can be done in the course of a decade. A high standard of living can come only from massive industrialisation and from a complete transformation of the agricultural economy. An attack on poverty is thus synonymous with an accelerated process of growth.

In thinking of growth what matters is its composition in relation to a given set of social objectives. It is obvious that if we have a kind of growth in which good quality education is available only to the few, if we have a kind of growth in which the benefits of modern medical sciences are concentrated in the urban areas, if we have a kind of growth in which industry churns out goods which cater to the tastes and needs of a privileged minority, then we are not only moving farther away from the goal of removing poverty, but are in fact placing serious limits on growth itself. For such a pattern of growth means that we are not making the most of our human resources; it means that we are not preserving and strengthening the productive capacity of our most valuable resource, namely our population taken as a whole; it means that we are restricting the scope for industrial expansion by limiting the market for industrial products to a numerically insignificant part of the national community. Let me admit that to a certain extent these distortions have in fact crept into our pattern of growth. Why and how has this happened? This is a question which bothered Nehru a great deal and long before the present debate started, he appointed a high-powered committee to go into this question. I would be less than truthful if I did not point out at this stage what seems to me to be the basic reason for the paradox that a growth pattern conceived within socialist categories of analysis should result in a consumption pattern which bears, in many respects, resemblance to the patterns obtaining in capitalist societies. It is important to go into this question because otherwise there is some danger that our analysis may be clouded by a vague welfarism.

It should not be forgotten that the modernising role in Indian society was, due to historical circumstances, appropriated by the intelligentsia, whether in the professions or in the civil services or in politics. Initially, this intelligentsia performed a historically progressive role, in attacking superstition, in waging a relentless fight against sterile traditionalism and retrogressive social values, and in welcoming science and technology and its dissemination among the people. Its social and political thinking was moulded by Nehru and it accepted the goal of a modern progressive society with great enthusiasm. But as a class, it was not revolutionary in origin. It was at its best a liberalising force. As time went on, it lost the kind of elan that had characterised the Indian renaissance. By the time independence came, it had assimilated into its ethos the badly learnt and even more badly digested lessons of the astounding success of the middle-class revolutions in European societies. What it learnt to admire most was the consumer-oriented ethic of mature industrial economies. What it ignored was the sweat and the toil that had gone into the making of the consumer paradise which glittered and tempted the unwary.

Superimposed upon this intelligentsia was the political process in which the vast masses of the people participated, but which could be manipulated at will by the power that money wields. The sanction of massive electoral support gave to Nehru and to Mrs Gandhi the political authority to determine the broad strategy of development, but it was possible for the intelligentsia, which constituted the bulk of the higher civil service, of the professions and of the leadership in the defence forces, by acting in concert with the more organised forces representing private business and the kulaks in the rural areas, to deviate from the basic design of development and to introduce principles and concepts that ran counter to the basic aims of development. Fearful of open opposition to the strategic aims of development as formulated by Nehru, the formidable alignment of forces which I mentioned above found it prudent to lodge itself in the numerous nooks and crevices of our political and administrative system, to mount its counteroffensive from under the cover of laws, rules, regulations and procedures of a system that had grown in response to the requirements of predatory colonialism. It has taken a long time to embark on new policies like bank nationalisation. It needed a full-blown social and economic crisis in the wake of the devaluation of the rupee to correct the direction of economic and social development. I have, however, invited your attention to some of the sociological aspects of our present malaise to underline two points. First, the present parliamentary system, and its institutions of democratic control are inadequate from the point of view of mass participation in the implementation of the plans. The massive shift of opinion in favour of a more radical orientation to our growth pattern highlights the urgency of securing such participation, so that the manipulation of the economic and social processes with a view to distorting our priorities is checked. Secondly, the intelligentsia itself must resume its historically progressive role or else it must be prepared to fade into insignificance. The forces of change released by the processes set into motion by the five-year plans are insistent, compelling and durable. They cannot be wished away. They demand that they be integrated into the framework of development in the seventies, not in name but in substance.

This speech is an extract from D.P. Dhar’s ‘Planning and Social Change’, Arnold Heinemann Publishers, New Delhi: 1976.