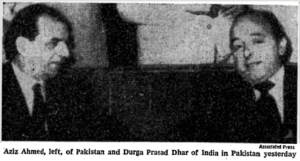

NEW DELHI, April 26 —During the six years that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi has been in power she has used many people as her emissaries for various tasks but there has been no one like Durga Prasad Dhar, who is her principal envoy to the talks that opened with Pakistan today in Murree. Like Henry A. Kissinger, Mr. Dhar appears to be a perfect fit in his role. In a short period he has emerged as Mrs. Gandhi’s foremost confidant, troubleshooter and conscience‐keeper. As chairman of the Policy Planning Committee of the Foreign Ministry, Mr. Dhar is at the apex of the triumvirate of Kashmiri Brahman advisers to Mrs. Gandhi, herself a Kashmiri Brahman.

At the bottom are Foreign Secretary T. N. Kaul and P. N. Haksar, the Prime Minister’s private secretary. Mr. Kaul and Mr. Haksar are associated with many decisions Mrs. Gandhi makes, but Mr. Dhar seems one step above them — he makes decisions for her.

Although the 53‐year‐old official has been a political celebrity in his home state for nearly two decades, he shot into national prominence when he was sent to Moscow as India’s Ambassador in 1968. Diplomacy was new to him, and his critics predicted that he had gone to meet his Waterloo.

He Returned as a Hero

Two years later Mr. Dhar returned home a hero, having brought New Delhi and Moscow together. When he was named chief policy adviser on foreign affairs, many ministry officials were chagrined and Mr. Kaul went on leave in protest, but he later returned, reconciled to Mr. Dhar’s importance.

Mr. Dhar is credited with the entire strategy for Indian action in what was then East Pakistan. On his first visit to Dacca after the territory became independent last December, he celebrated the event at a party at the Inter‐Continental Hotel that lasted until the early hours, with the result that he had to cancel a news conference because of “indisposition.”

A tall, handsome man with a taste for the good things of life, he enjoys a drink (his favorite is Scotch), Urdu poetry and music. Although branded by his critics as a stanchly pro‐Moscow leftist, he is no Communist. His only loyalty is to his leader, and he prefers to be the power behind the throne.

Durga Prasad Dhar—D. P. to his friends—was born in Srinagar on April 24, 1918, the only son of an affluent family that had long been close to the kings. However, he detested the pomp and feudal surroundings and became a rebel. When he was 17 he joined a student movement, of which he became president. His parents frowned on his adventure and gave him up as a loafer.

After graduating in arts from Srinagar University, he went to Lucknow University in Uttar Pradesh for a law degree. There he came in close contact with Jawaharlal Nehru and made a good impression on him—a vital factor in his later career.

Mr. Dhar returned to Kashmir but failed as a lawyer. He then joined the nationalist movement headed by Sheik Abdullah, the Lion of Kashmir. He also married and had a son, now a prosperous businessman.

When Pakistan sent troops to seize Kashmir after the subcontinent was partitioned in 1947, Mr. Dhar flew to New Delhi to persuade Mr. Nehru, then Prime Minister, to accept the accession offered by the Maharaja of Kashmir and move Indian troops to save the territory. Mr. Nehru, worried about international opinion, was hesitant at first, but Mr. Dhar, who had the full backing of Sheik Abdullah, prevailed.

Joined Abdullah’s Cabinet

Mr. Dhar became a deputy minister in the cabinet of Sheik Abdullah. Mr. Dhar became Home Minister when Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed succeeded Sheik Abdullah as Prime Minister in 1953. In 1963 Mr. Dhar, resenting the Prime Minister’s dictatorial ways, joined with his adversary, Ghulam Mohammed Sadiq, who took over the government. Then Mr. Dhar fell out with Mr. Sadiq too and left Kashmiri politics to find a place on the national scene.

Because of his fast living Mr. Dhar is reported to have heart and kidney ailments, but at a moment of crisis he can be a human dynamo.

“He is like an easy‐going, indulgent Mogul nobleman,” a colleague remarked, “but he has the most extraordinary modern mind I have ever come across.”

This article was originally published on 27 April 1972 in The New York Times. Read here.